Lawsuit filed against Jackson County Police Department for inmate’s death from “prolonged lack of attention”

“Josh McLemore wasn’t a criminal. He was mentally ill and in crisis. He was out of touch with reality and needed help,” said Hank Balson, an attorney for McLemore’s family.

April 17, 2023

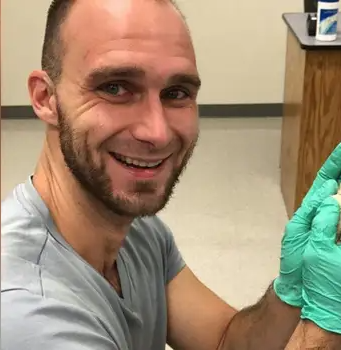

Jackson County inmate Josh McLemore died August 10, 2021 in Jackson County Jail custody from multiple organ failure as a result of severe dehydration and starvation. A lawsuit was filed earlier this week by McLemore’s family, stating that his untimely, brutal death was a result of constant mistreatment and neglect by department guards and officers.

McLemore was originally hospitalized at Schneck Medical Center for a mental health crisis after being found naked and lying on the floor of his Seymour apartment, completely incoherent. He struggled with episodes of schizophrenia, and his family believed the hospital could help him navigate his mental health crisis. During his stay, he was never given any mental health screenings or intake forms, but instead was thrown into jail after pulling a nurse’s hair.

After being taken into Jackson County Police custody on July 20, McLemore, was thrown into a small, windowless solitary confinement cell. He would only leave this cell when he was too severely malnourished to survive.

McLemore, never receiving any help with his still ongoing mental crisis, spent his time in his cell completely naked chewing styrofoam, rolling in his own feces, and licking the walls around him, refusing to eat any lunch or dinner provided for him. At one point, McLemore was strapped into a restraining device that completely bound his arms and legs and was left in this position for over four hours. Footage of McLemore’s cell shows that he rarely displayed physical resistance towards officers, and the reasoning for and duration of this binding was unclear.

He often asked himself, “Where am I?” throughout his incarceration, showing obvious signs of a prolonged psychosis that went untreated. Because of his mental state, McLemore was put on “medical observation,” in which prison guards are ordered to keep logs regarding an inmate’s mental and physical health. For McLemore, these logs were only written for 7 1/2 out of the 20 days he was jailed. The only medical professional McLemore met with was a licensed practical nurse who talked with him for less than two minutes. After their discussion, she threw a Gatorade bottle at him “the way one would toss a piece of meat to a wild animal in a cage.”

McLemore resided in this cell for almost three weeks, with extremely limited interactions with prison staff. Over the course of his confinement, he lost 45 pounds and became completely emaciated. Guards only showed concern for his health 20 days after being imprisoned and eventually called medical authorities to give him an evaluation. On August 8, one jail personnel sent a text to another describing McLemore’s condition: “Honest to god, this josh mcelmore (sic). Has the court said anything about getting him out of here … he can’t hold his hands, legs anything. He’s dead weight.”

On this same day, he was transported to Schneck Medical Center, where he was unable to receive proper treatment as a result of the severity of his physical and mental state. He was airlifted to a hospital in Cincinnati, but died before he could be treated. Organ failure was cited to be the primary cause, rooted in starvation and his “altered mental status and untreated schizophrenia.” Josh McLemore’s mother, Rhonda, passed 16 months after her son’s death due to heart issues, family members saying “his loss devastated her.”

A report was released last year regarding an investigation of McLemore’s death, but Jackson County Prosecutor Jeffrey Chalfant did not hold any jail officials criminally liable, even though he stated that McLemore “most likely died due to a prolonged lack of attention” by the jail and its staff.

McLemore’s aunt, Melita Ladner, is the filer of the lawsuit, with Jackson County Sheriff Rick Meyer, Jail Commander Chris Everhart, and private health contracting company Advanced Correctional Health, Inc., listed as defendants.

This instance of inmate abuse and a lack of accountability is not isolated. Less than a month before McLemore’s death, Ta’Neasha Chappell also died after being in the Jackson County Police Department’s care after hours of begging for help and medical attention. After repeatedly vomiting up blood, she asked to be taken to the hospital for almost 16 hours, with guards repeatedly ignoring and snapping at her demands. Multiple other inmates tried to ask for help for her, as she eventually was too unwell to ask for assistance. She began her pleading around 8:30 p.m. on July 15, but EMS was only called around 4:00 p.m. the next day. She was taken to Schneck Medical Center, but died there almost two hours later.

An autopsy found that the cause of her death was “probable toxicity,” theorizing it might’ve been from another inmate. Poisoning can be reversed, as long as medical attention is sought out immediately. Prison personnel failed to do this.

Prosecutor Chalfant also held no one accountable for Chappell’s death in the hands of Jackson County Jail. Chappell’s family has also filed a federal lawsuit against Jackson County Jail personnel, including Jackson County Sheriff Rick Meyer, Jail Commander Chris Everhart, and other jail employees.

If you have any opinions you would like to voice to any of these officials, messages and calls for the Sheriff can be sent to https://www.jacksoncountysheriffin.org or 812-358-2141. Jackson County Prosecutor Jeffrey Chalfant’s office can be reached at 317-232-1836 or [email protected].