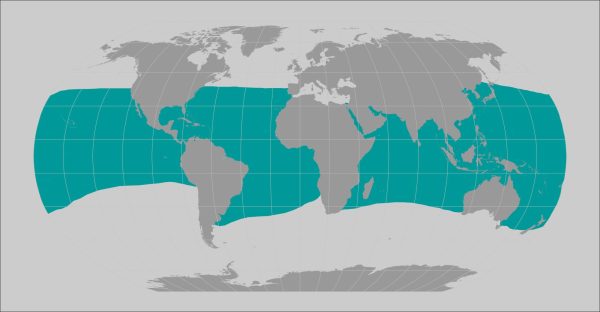

Named after “blanket” or “cloak” in Spanish, manta rays are cartilaginous fish (fish without bones) that have an oddly triangular shape. Lacking bones, their skull is composed of cartilage, making it flexible and lightweight, which supports their method of consumption with their giant mouth. They’re often confused with stingrays, but there are two distinct differences: the lifestyle of both and the fact that stingrays have a stinger. There are three species of manta rays: reef manta rays, which typically live near coastlines and don’t move too much, reaching up to 11.5 feet; pelagic manta rays, which swim through the oceans and reach up to 23 feet; and Atlantic manta rays, which live in the Atlantic Ocean.

Compared to any other fish in the ocean, manta rays have the largest brain relative to their body size and are highly intelligent: some studies even suggest that they’re self-aware. Not only that, but they’re considered keystone species in many habitats, controlling plankton populations by filtering coral reefs. Despite manta rays being so big, their prey, plankton, is the smallest form of marine life. To get the most food per ‘patch’ of plankton, they often spin around in circles to get more flowing into their mouth. They usually swim at speeds of 3-6 mph but can reach burst speeds of up to 22 mph, obtaining oxygen as the water passes through their gills.

Additionally, Manta rays don’t only have eyes–they can sense weak electrical signals using electroreceptors, located on the underside (also called the “ventral”)! They also have spiracles–small holes behind their eyes–to help them pick up vibrations in various sources. The skin of manta rays are covered in tiny, tooth-like structures called dermal denticles; they reduce drag and may have sensory functions, too.

With the skin of a manta ray, no two are alike: they develop patterns. Some patterns are bold and obvious, while others are subtle. They form during the early development of a manta ray’s life, but can fade with age. Some markings come from boat or fishing encounters.

Speaking of fishing encounters, the manta ray’s main threat is overfishing. Though they’ve evaded being the target species for hunters in the past, recently the market and demand for manta rays have increased. They don’t reproduce fast enough to keep up–they grow slowly and reproduce little. On top of this, plastic is also an issue: while filtering for plankton, plastic can get sucked up. With particles like sand, they can vomit it up, but plastic may be sharp and cause damage to them.

Despite the demand for manta rays increasin g, scientists have worked to protect them, recently forcing countries to prove that their method of hunting manta rays is sustainable, and countries like Peru and the Philippines have put laws in place to protect them. Manta rays aren’t only in those two areas, of course. They range all across the world and are still being studied, so next time you’re out swimming, keep an eye out for one.

g, scientists have worked to protect them, recently forcing countries to prove that their method of hunting manta rays is sustainable, and countries like Peru and the Philippines have put laws in place to protect them. Manta rays aren’t only in those two areas, of course. They range all across the world and are still being studied, so next time you’re out swimming, keep an eye out for one.

Sources:

(2025). Giant Manta Ray. NOAA Fisheries. https://www.fisheries.noaa.gov/species/giant-manta-ray.

(2025). The fascinating anatomy of manta rays. Manta Ray Advocates. https://mantarayadvocates.com/anatomy-of-manta-rays/.

De Vos, Lauren. Manta rays. Save Our Seas. https://saveourseas.com/worldofsharks/manta-rays.